The newly appointed French Prime Minister and former Brexit negotiator, Michel Barnier, promised in his first speech at the National Assembly, to reduce the astronomical French debt. And he then warned that his government would “work out no miracles”.

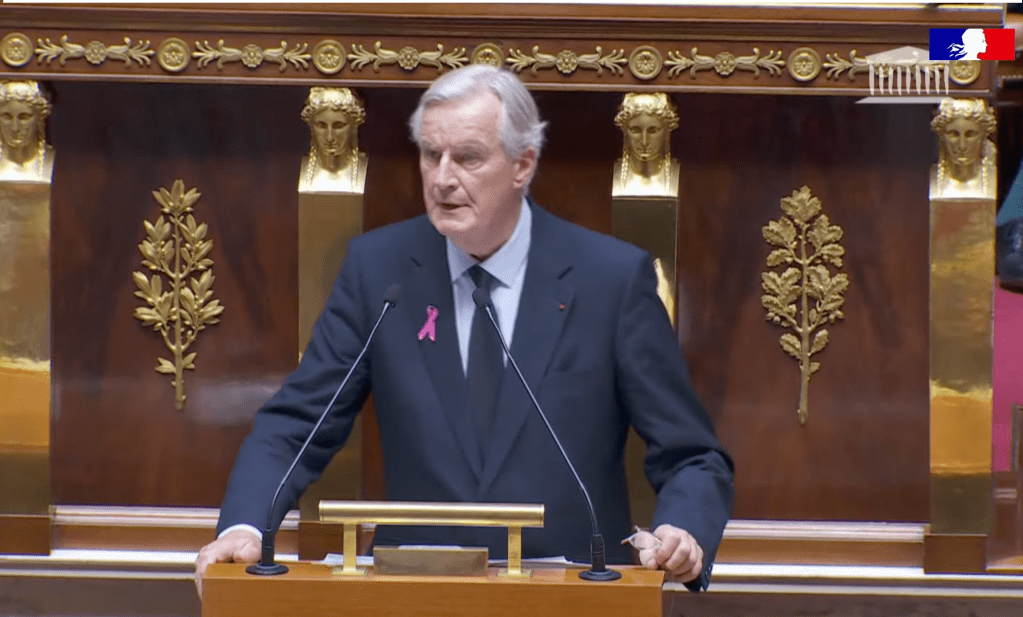

At the National Assembly on Tuesday afternoon, the French PM, Michel Barnier issued a rather modest speech in front of the French MPs (députés), who were sitting for the first time since the summer recess, five months after the June snap elections.

Gathered in the hemicycle, none of the MPs were really cheerful or enthusiastic and one thing is clear: they were not expecting a victorious-like speech from the PM.

And there was indeed nothing to celebrate for Michel Barnier, who was appointed PM by President Macron last month to form a coalition government after Macron’s party, Renaissance, lost the last-minute snap elections in June.

During his solemn and rather lengthy speech (an hour and twenty minutes), Barnier displayed the main policies his government will lead in the forthcoming months.

His main concern was clearly France’s colossal debt, which has broken historical records this year, reaching the figure of €3.288 trillion, 6% of France’s GDP in September. He compared the French debt as a “Damocles sword”:

“The true Damocles sword is here and now suspended upon the French people and if no action is taken, because of a lack of courage, I’m sure of one thing: the national debt will weigh much heavier tomorrow on our children and our grandchildren’s shoulders.”

The MPs from the far-left party La France insoumise tried to interrupt the PM several times, blaming Macron, Bruno Le Maire, the former finance minister and Gabriel Attal, the former PM, for this situation.

The reasons for the debt’s huge increase in the eight past years were in fact named by the PM: the billions of subsidies distributed by the French social system, sometimes regardless of one’s financial resources, subsidies given to workers and pensioners during the pandemic which costed billions, the generous health system and the waste of money by various ministries and local councils.

The cost of the national debt is now the French government’s second highest budget, €51 billion after education.

When Macron arrived in power in 2017, the national debt was already quite high indeed, €2.280 billion. Since then, public borrowing has been going up every year, despite Macron’s promise to diminish it.

Moderation and consultation

Barnier showed one quality his predecessor probably lacked which is his greater willingness to work with all the parties represented in parliament, at least with those who are willing to do so:

“I shall ask my government to rely more on parliamentary work: bills, amendments, recommendations from the inquiry or information committees, assessment of public policies.”

While Macron still had a majority in parliament, he could pass as many bills as he wished, without bothering too much about his MPs’ claims or ideas. The National Assembly was thus seen as the Élysée’s “Chambre d’enregistrement” where no important decisions could really be made.

The 5th Republic’s constitution states that the PM is in charge of presiding over the government. But in practice, the PM’s figure has often been overshadowed since 1959, mainly because of De Gaulle’s dominant personality.

Things will of course be quite different now that parliament is mainly opposed to Macron and that Barnier himself is not a political ally of the president.

Marine Le Pen’s warnings

More moderate in her speech than expected, the leader of the National Rally, Marine Le Pen nearly supported the newly formed government and its PM, at least in some areas.

Before that though, she heavily criticised Emmanuel Macron, whom she named as the “discredited head of a collapsing minority”. She then qualified the coalition government and its parties as a “coalition of abyss”.

These remarks were unambiguous references to the National Rally’s size since the snap elections. It is now the largest single political group with 123 seats, far from enough though to form a government.

Marine le Pen then promised her party would “refuse to topple” Barnier’s government “to give him a chance, however thin it may be, to take at last the right measures needed for the country’s recovery.”

She emphasised unsurprisingly on immigration, along with the scrapping of the last government’s bill on pensions, the tackling of insecurity and the reduction of the public debt.

The fact the RN is willing to support the government is certainly a relief for Barnier who is only fully supported by 120 MPs out of 577.

Michel Barnier, though in a delicate position, is certainly in a more favourable one than Attal was: he is seen by all parties as a respectable veteran of French politics (73 years old) and he has never been involved in any of Macron’s governments in the past eight years.

During his former role as Brexit negotiator from 2016 to 2020, he also managed to gain the respect of most of his European counterparts.

Barnier’s challenge in the following months will be to avoid at all costs a coalition far-right and far-left coalition to trigger a non-confidence vote.

For now, this outcome seems rather unlikely considering the profound animosity between the National Rally and France insoumise.

Leave a comment